Women's Place in the Digital World: Fandom as Community

|

| 1919, Iowa State College, women work on student publication |

Being a fan of something is not a modern concept, nor is it unique to niche realms of society, yet it is a concept that has become highly politicised. Who likes what and how these people engage with cultural products that they enjoy does not just stir debate - it can lead to abuse and even violence. From the basic stereotype of a nerd being the subject of jokes in television shows to threats of violence delivered through social networks, being involved in fan communities is not a simple pass time, rather it is inherently political and involves engaging with contested spaces and potentially opening one's self up to abuse and prejudice. Yet, at the same time, fan communities are just that - communities, and they have shown to be spaces where minority groups can have a stake in the internet and partake in culture. Women have a big role in fan communities and in particular are major creators and consumers of fanfiction. Fanfiction has become a vibrant site of engagement for women who feel marginalised in other realms of culture and the internet. Of course, fanfiction is not just a site of engagement and community, it is also a site where women can actively partake in culture, writing the female gaze into existence one post at a time.

Roots: Jane Austen Moves with the Times

The notion of fandom - being passionate about and engaging with an aspect of culture - is not a new idea, but its arrival in new media has centred it in debates about fandom and women's roles and spaces. Fandom extends from sports to movies, to collectable toys, to celebrities, encompassing all types of culture from the very niche to the widely accepted. Fandom is not a by-product of new media: it existed prior to this and still continues to exist outside of the internet. In many cases the two spheres of analogue and new media coexist quite naturally as people put posters on their bedroom walls as they listen to streamed music, collect trading cards based on popular television shows or write on fanfic.net about their favourite books. Fanfiction also predates new media, and thrived through the creation of zines and other independent publications. With the arrival of the internet, fanfiction was quick to take advantage of new platforms for engaging with and sharing content: these early platforms included ListServ technology and forums before expanding into blogging platforms such as LiveJournal and dedicated fanfiction websites such as fanfiction.net and archiveofourown.org (Busse & Hellekson, 2006, p. 13-14). The expansion into new media achieved several things: it opened up a space for yet more engagement, for those above the digital divide (it's free and simple to create an account and upload your own fanfiction to any number of sites) thus expanding on the community of fanfiction. As Busse and Hellekson argue (2006), new media is able to transcend geographical boundaries that analogue media could not thus making fanfiction accessible to younger and more diverse audiences (p. 13-14).While the internet has dramatically changed the face of fandom - Busse and Hellekson (2006) call it 'the most important technological advance, the one with the farthest-reaching implications' - it is a falsehood to see fandom, and specifically fanfiction, as something as a symptom of new media (p. 13). It is also, therefore, a falsehood to see the creations of derivative texts as something solely the realm of 21st century fanfiction writers, engaging the tools of new media. Derecho (2006) describes fanfiction as drawing upon the open archive of a source text and in this sense compares modern day fanfiction to the types of works that were spawned by the success of Jane Austen, for example (authors Linda Berdoll and Pamela Aidan are just two examples of authors who wrote in Austen's worlds) (p. 65). Derecho (2006) argues that the roots of fanfiction can be found in 17th century literature that was derivative for the purpose of writing culture anew (p. 67).

So, having established that the realm of fanfiction, or derivative works, are not new, it is important to understand the role of the internet in fandom as one of creating space for minority communities and also as one of projecting these spaces into the public sphere. These are the twin dynamics, or challenges, of modern fandom, but as Minkel (2014) states, 'fandom as community, as a deeply supportive space for women and girls, can honestly make a life-changing difference for a person hovering on the margins'. This crucial idea sits alongside the challenges that women face online.

Contested Community: Women Don't Belong in Online Spaces

There's a special ire reserved for the particular corner of the web where people make transformative works about the media they love — and given that this corner is primarily composed of young women, it's hard to avoid the conclusion that this ire is gendered (Grady, 2016).As Grady (2016) describes, the fact that women are taking up space on the internet is controversial: debates (and outright abuse) hover around women producing fanfiction, playing games, sharing their opinions and - sadly - generally existing in online spaces. Alongside this, we see a lack of female representation across texts, women are shunned for speaking out against female representation or are simply ignored, as is the case of women as sports fans. Meadows (2014) describes the challenge of being a women online, stating that 'the act of simply being female in predominantly or traditionally male spaces is always and inherently an intolerable provocation'. When it comes to the production of fanfiction the arguments quickly grow to encompass not just what women should like and how they should like it but what women are entitled to produce and whether that content is of any relevance - arguments are often centred around how boring and uncreative fanfiction is. This is in spite of the fact that much fanfiction remains the domain of hobbyists who just want to engage with and enjoy the texts that they are passionate about. Grady (2016) argues that, 'young women are so attacked for loving the media they love that it is a radical act for a young woman to love something unashamedly' - and when they do, they open themselves up to abuse.

These condescending debates do little to discourage the producers of fanfiction, but sadly it doesn't stop at condescension: online abuse and exploitation seems to come with the territory. A shocking example of the abuse of female fans was shared by Anita Sarkeesian, a media critic and gamer, who received an outpouring of violent abuse and threats when she started a fundraising campaign through Kickstarter to look at the way women are represented in video games. Sarkeesian (2012) described the attack as a 'massive online hate campaign' which was incredibly personal in nature (2:28). Sarkeesian's attempt to explore women in games was met, not just with resistance, but with violence in an attempt to 'maintain the status quo of videogames as a male dominated space' (5:40). While Sarkeesian's attack might be an extreme example, abuse is not uncommon online and this is something that differentiates analogue and new media - new media puts women on the world stage (unlike the fanfiction zines of yesteryear) where the possibility of becoming a victim is very real. Yet, as Sarkeesian (2012) describes, while it can be dangerous to navigate contested online spaces, it also presents an opportunity to fight back - and this is done primarily as a community. Despite the abuse, Sarkeesian's campaign was an unprecedented success and her project grew from a few simple YouTube videos to a major education platform, through the power of crowdfunding.

The Community Rallies: Women are Here to Stay

While the internet remains a contested space for women, it still provides a community environment and women use this in numerous ways to engage with popular culture and connect with other fans. This engagement takes on a number of forms but by and large involves rewriting popular stories to include different voices or characters. These transformative works fulfil a number of functions as they allow women a voice in cultural spaces often dominated by men. As Grady states, 'it's a place where young women love their media without reservation, and where they can make stories for themselves'.

New media has played an interesting role in the development of fanfiction: convergence culture has led to many new layers of engagement with media texts. As much of mainstream media is still dominated by a (predominantly white) male gaze, fanfiction has provided an opportunity for women to write themselves into culture, in a community setting. An example of this is Lord of the Rings fanfiction: both J. R. R. Tolkien's novels and Peter Jackson's movies have few female characters and so women have taking to writing fanfiction that fills this gap. As Viars and Coker (2015) describe, '[in the series] there seems to be little space left over for women with their own independent agency or ability to traverse across geographic or metaphysical boundaries as the men do' (p. 40). Online sites provide a space to explore these ideas with other women. As Minkel (2014) states, 'fan fiction gives women and other marginalised groups the chance to subvert that [male] perspective, to fracture a story and recast it in her own way'. Of course, Lord of the Rings is just one example of women transforming canonical works for their own pleasure - fanfiction has been written about almost every modern television series, film and popular fiction novel available. Bury (2005) describes the relationship between women and texts and men and texts as different. She states that 'even today, as any visit to a bookstore will confirm, action, adventure and science fiction narratives are deemed appropriate genres for boys while romance and other relationship-centred narratives are posited as suitable for girls' (Bury, 2005, p. 42). It's clear from the abundance of fanfiction, however, that women engage with all types of genres and in many they are largely under-represented.

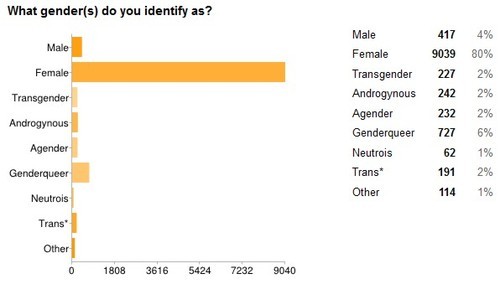

|

| Archive of Our Own users were surveyed regarding their gender |

Surrounding the creation of fanfiction and all of its diverse and expressive content is a large community where many people find friendship and establish connections with like minded fans. Coppa (2006) describes media fandom as 'bigger, louder, less defined, and more exciting that its ever been' (p. 57). She goes on to describe how the internet has revolutionised the potential for fandom: fanfiction, visual art and digital media (such practices include vidding - making music videos) all contribute to fandom (Coppa, 2006, p. 58). In this expanded world of fandom there is space for diverse communities to engage with the media texts they are passionate about. The dynamics of internet spaces are somewhat counter-intuitive - in the same moment that women, like Sarkeesian, are attacked for their gender, women are finding sanctuary in online spaces as they forge communities with other women. Bury (2005) describes how this began in the early days of the internet: 'facing varying degrees of harassment and denigration on the male-dominated forums, many female fans chose to stake out and colonize [sic] cyberspaces of their own' (p. 2). In 2018 it seems that women are well-established residents of the digital sphere - just one site, fanfiction.net, has over 2.2 million users and stories posted in over 30 languages. While a dark corner of the internet is determined to keep women out of online spaces, many women are busy writing themselves into stories of all kinds, having their say and establishing connections. As prominent author Rainbow Rowell states, 'fandom and the internet really just give people a chance to find each other' and share the fandom they've been engaging with all along (Nguyen, 2015). Rowell is an example of someone who dispels many of the arguments lodged at women - she has published several novels, actively engages with fanfiction and even wrote her most recent novel about fanfiction (and as new media goes, numerous fanfiction has been written about her novels).

|

| Fanart from Rainbow Rowell's 'Carry On' by Dancing with Dinosaurs |

Despite its challenges, women are unrelenting in creating space online to engage in fandom - to explore texts they enjoy, create narratives that are relevant to them and develop community. Through male-dominated culture and spaces, women have worked to establish community and a culture with a female gaze. At the same time, the breadth and power of the internet has enabled women to proliferate online - taking up space and sharing in a wide range of fandom.

References

Bury, R. (2005). Cyberspaces of their own: Female fandoms online. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing.

Busse, K. & Hellekson, K. (2006). Introduction: Work in progress. In K. Hellekson, & K. Busse (Eds.), Fan fiction and fan communities in the age of the internet (pp. 5-32). Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

Coppa, F. (2006). A brief history of media fandom. In K. Hellekson, & K. Busse (Eds.), Fan fiction and fan communities in the age of the internet (pp. 5-32). Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

Derecho, A. (2006). Archontic literature: A definition, a history, and several theories of fan fiction. In K. Hellekson, & K. Busse (Eds.), Fan fiction and fan communities in the age of the internet (pp. 41-59). Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

Grady, C. (2016, June 2). Why we're terrified of fanfiction [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/2016/6/2/11531406/why-were-terrified-fanfiction-teen-girls

Meadows, F. (2014, January 15). Seeming female: Gender in digital spaces [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://fozmeadows.wordpress.com/2014/01/15/seeming-female-gender-in-digital-spaces/

Minkel, E. (2014, October 17). Why it doesn't matter what Benedict Cumberbatch thinks of Sherlock fan fiction [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/2014/10/why-it-doesn-t-matter-what-benedict-cumberbatch-thinks-sherlock-fan-fiction

Nguyen, K. (2015, October). The Rainbow Rowell theory of fan fiction [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://review.oysterbooks.com/p/KY5rRj4Bw9eg6fGJ8JQvE4/the-rainbow-rowell-theory-of-fan-fiction

Pellegrini, N. (2017, February 14). FanFiction.Net vs. Archive of Our Own [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://hobbylark.com/fandoms/fanfictionnet-vs-archive-of-our-own

Sarkeesian, A. (2012, December 5). TEDxWomen talk about online harassment & cyber mobs [Video file]. Retrieved from https://feministfrequency.com/video/tedxwomen-talk-on-sexist-harassment-cyber-mobs/

Viars., & Coker. (2015). Constructing Lothiriel: Rewriting and rescuing the women of Middle-Earth from the margins. Mythlore 33(2), 37-50.

Comments

Post a Comment